When I cook a dish out of the ancient Roman cookbook called Apicius, I never know exactly what I’m going to get. And that’s the beauty of it. The combination of flavors, textures, and odors is very different from what you find in contemporary Italian cuisine; in fact, it’s unlike anything our modern palates are used to. Each recipe is a small adventure, resulting in a salutary sense of disorientation at your own dining room table.

Yesterday, for example, I gave Aliter Patina Versatilis (Apicius IV.II—2) a try.

In ancient Rome, a patina was a round or oval pan, of varying depths, used to cook egg-based dishes in embers (by extension a patina is any dish cooked this way; it usually comes out looking like an omelet or a frittata). I roasted a two cups of hazelnuts, walnuts, and a tbsp of peppercorns in the oven, and then ground them into a paste in a mortar, pouring in olive oil and an equal dose of honey and garum. (The mortar and pestle were the Oster/Cuisinart of the ancient world; crushing this way provides far more control over the end product, and, as a bonus, a sound wallop of shoulder pain. Which reminds you that most of the chefs in ancient Rome were enslaved Greeks.) In a mixing bowl, I added four eggs, and then I cooked the lot in a cast-iron frying pan over low heat—simulating embers—on the stovetop for 25 minutes. Then you flip it over onto a plate (hence the “versatilis”)—making this an Upside-Down Nut Custard, I suppose.

The result was an unappetizing-looking but strangely delicious dish that was neither custard nor omelet, yet somehow mingled savory-umami-and-sweet in a way that pushed sensory buttons I didn’t even know I had. This patina was a culinary centaur: not dessert—too savory—but, thanks to the honey, too sweet to be a main course. My wife Erin, who is usually stand-offish about my flamingo-and-dormice experiments, declared this one a success. We gobbled it up. (Our sons, who are in a non-adventurous phase, held out for leftover Simpsons donuts from Bernie’s Beignes.) For me, the culinary realm of the umami (garum), acidic (sapa and other grape-derived condiments) and the sweet (honey) is where Roman cuisine excels, and where it has the most to teach contemporary chefs.

In last week’s dispatch, I described how I assembled a pantry of Roman ingredients. If you live in a big, multicultural city, you can probably do the same too without too much trouble. You can find translations of Apicius online, and there are cookbooks that provide tested recipes, complete with the quantities and cooking times Apicius is short on; Sally Grainger’s Cooking Apicius is one of the best, and Farrell Monaco over at Tavola Mediterraneana test-drives lots of Roman recipes (here’s her recipe for a pear patina.)

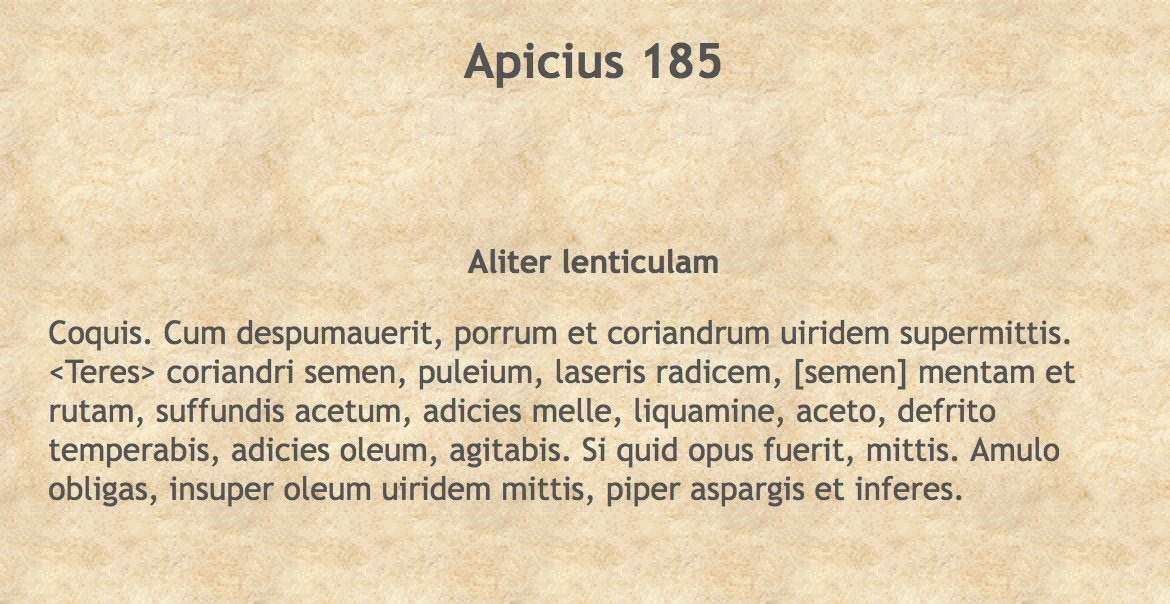

If you want to experience the flavor palate of ancient Rome, without going full-on sow’s vulva and skinned moray eel, a simple way to start is with good ol’ lentils. I’ll walk you through how I made a pot of delicious, nutritious, Aliter lenticulam (“lentils another way”). In Apicius, this is the whole recipe—basically a list of ingredients. I leaned on Sally Grainger’s adaptation to make my own.

"Cook the lentils, skim them, strain..." Keeping it Mediterranean, I used Greek lentils, about 300 grams, soaked overnight (not in the recipe, but, c'mon!)

"Add leeks..." Two medium, done and done.

"Crush coriander seed..." OK, about 20 grams should do. I’m using this hand-grinder I picked up in Istanbul, no need to go electric.

"Flea-bane, laser root..." Damn, all out of flea bane. And the good laser is in short supply, so I'm going to have to resort to Parthian laser, aka asafoetida, aka hing, aka the "devil's dung." Yes, it stinks (like a fart, as my 10-year-old tells me.) By the way, I’ve got a line on the real thing, but more on that in another dispatch.

I moisten the crushed spices and herbs (including rue) with red wine vinegar. After boiling the lentils and skimming off the scum, I add the leeks, which I sautéed in olive oil (from Crete!) along with a quarter tsp of shavings from the asafoetida balls. Then I add honey, also from Greece, and defrutum. I’d made some of my own, by boiling down red grape juice with figs, but this time I decided to use saba, a reduced must that I picked up in Rome. It’s like a balsamic vinegar before it sours, a unique flavor.

"Stir the purée until it's done..." (Could you be a little more specific, Apicius buddy?) Turns out it takes about 45 minutes to soften the lentils. I tossed in some fresh mint, even though the recipe calls for mint seeds—nobody's perfect. And the pièce de résistance, 2 tbsps of my home-fermented garum. (If you don’t have any on hand, use nuoc mam or some other high-quality Asian fish sauce.) Then, "Amulo obligas." Bind with roux...often interpreted as cornflour. Of course corn/maize is Mesoamerican, so the Romans never used it. But I'm getting hungry here, so look the other way, purists, because I'm throwing in a bit of Ye Olde Corn Starch to thicken.

Now the taste test—a bowl of lentils, scooped up with my own sourdough, made with the ancient grain known as khorosan.

That is complex. That is weird. That is great. The asafoetida brings something musty and onion-y. There's a deep umami thanks to the garum, which binds everything together. Sweet, fishy and salty—more like the SE Asian flavour palate than anything Italian.

There is amazing richness in Roman gastronomy, a richness I feel modern chefs have barely begun to explore. So many offbeat flavors, sensations, and textures: from pickled peaches to fried cucumbers to lettuce patinae. Cooking from Apicius is casual time travel to another culinary epoch, a little casual decadence for a quiet weekday night.

____

I’ve been writing these dispatches for a few months now, and I really appreciate everyone’s interest. This week’s post is intended for paid subscribers. (Free subscribers will still receive occasional dispatches by email.) If you want to continue receiving all the dispatches, please consider a paid subscription; this will also give you access to the archives, and allow me to continue my culinary experiments.