A visit to Gadir, the oldest city in western Europe.

// Before I learned to make my own garum, the fish sauce of the ancient world (aka garos, aka liquamen, aka haimation), I paid a visit to Cádiz, Spain. I’d heard that a team at the local university had replicated the sauce in the lab, and that chefs had embraced its use in their cooking.

Cádiz is actually west of the Pillars of Hercules—Gibraltar—so it’s on Spain’s Atlantic coast, rather than the Mediterranean. The conventional date for its founding, as GDR (Gadir), by the Phoenicians, is 1104 BCE. It was a great city to spend a week in: maritime-themed and very walkable. Here’s the view from my rooftop.

I met the team from the University of Cádiz at Balbo et Columela, an “Arqueofood” event space and mini-restaurant that happened to be right underneath the apartment I was staying at.

They very kindly set up a tasting of Flor de Garum, their version of garum, as well as oxygarum, a combination of vinegar and garum, ideal for salad dressings. A few Roman wines and paleo-Basque beers may have been consumed, too!

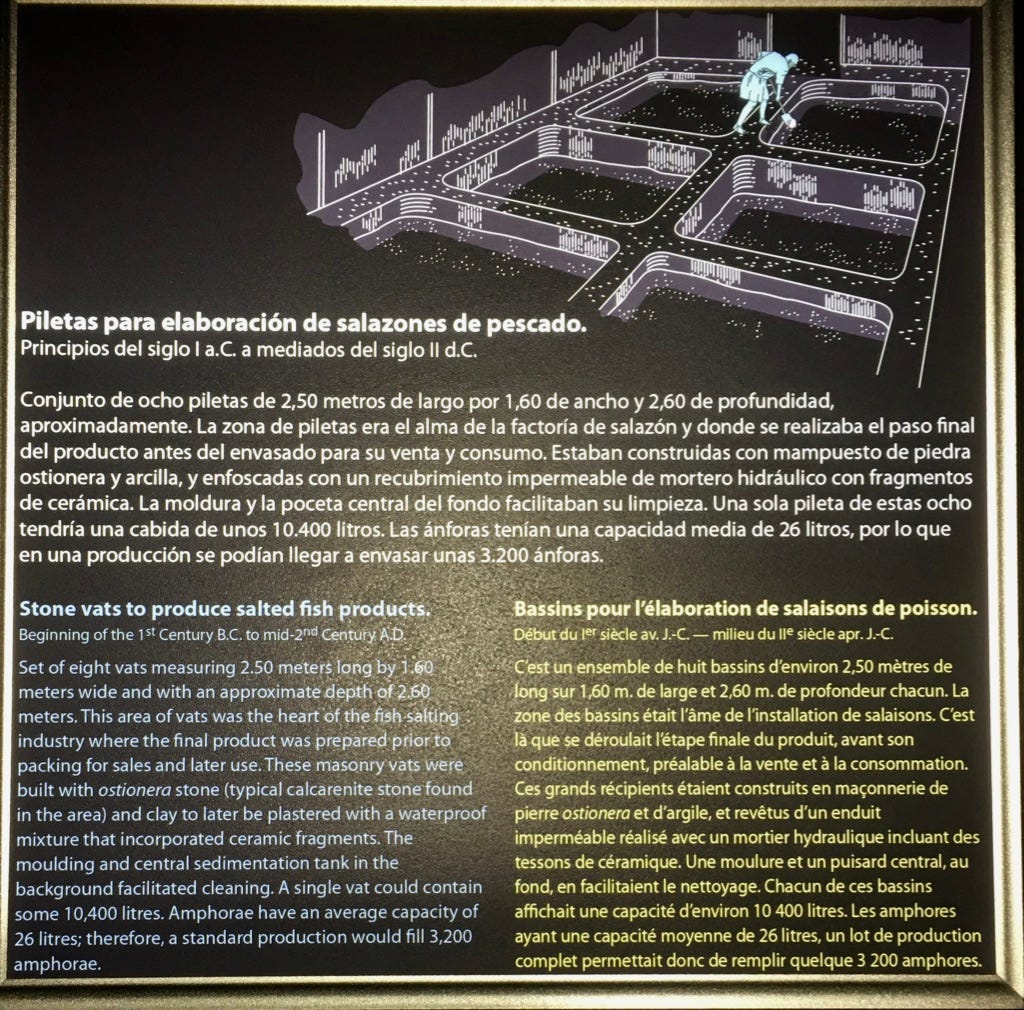

Earlier in the week I’d gone to the ruins of Baelo Claudio, an hour’s drive southeast, next to a nudist beach. The small city’s entire raison d’être was the manufacture of fish sauce. Large schools of bluefin tuna were caught offshore and salted down in complexes of concrete vats, cetariae, which still stand near the shore. Such cetariae were found from Turkey to Brittany, and some had vats large enough to salt down entire whales.

It was nice to be walking on Roman paving stones again, took me back to those weeks walking the Camino to Santiago…

It turned out I didn’t need to go to Baelo, though. The entire center of Cádiz was once a garum factory. The team from the university took me into the basement of the municipal theatre, where remains of fish salting vats dating from the 2nd century CE were found (as well as Phoenician ovens, and the bones of alley cats). They imagined the ancient city would have been ripe with the smell of fermenting tuna, mackerel, and sardines.

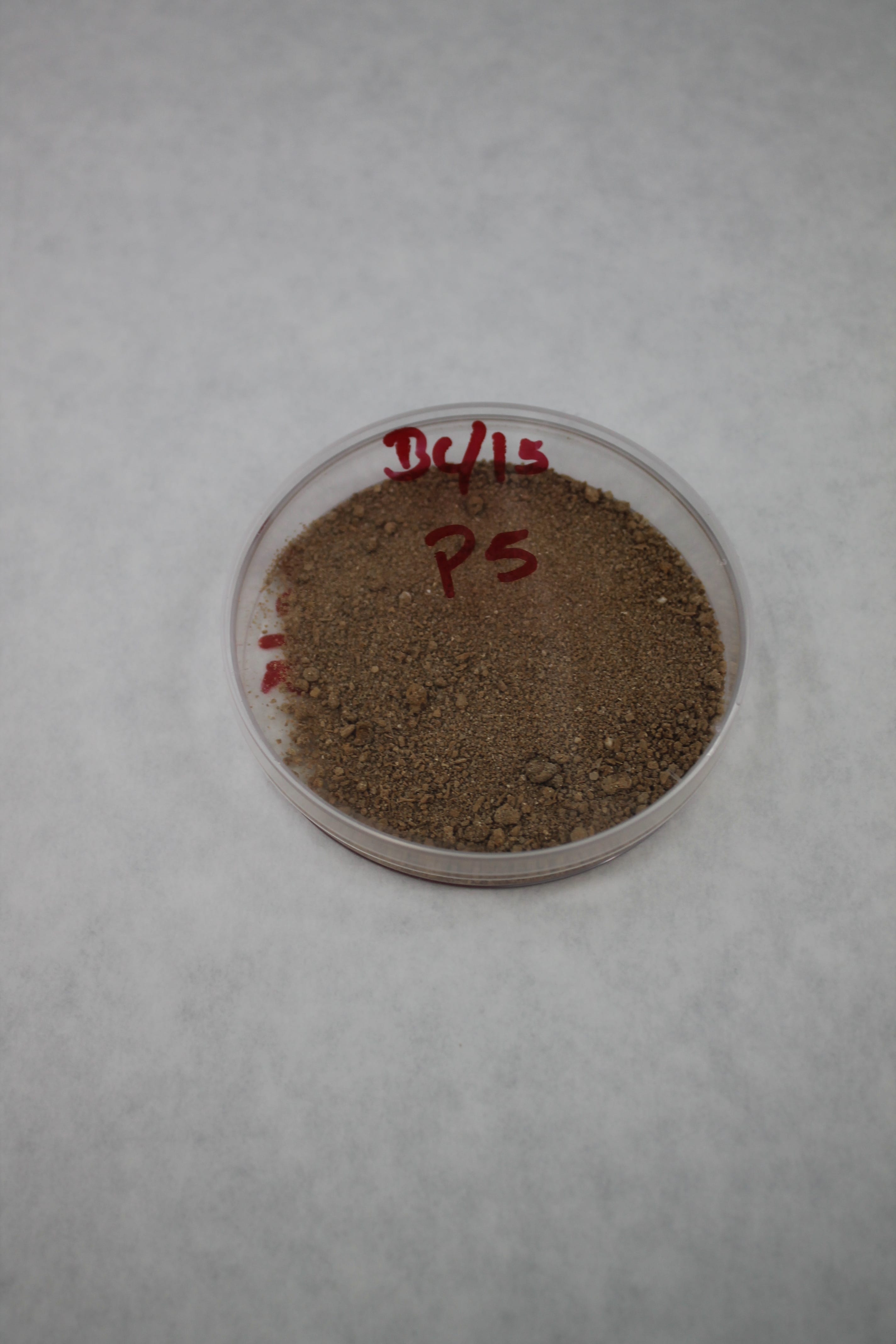

Next I took a bus ride to the labs at the university, where the team showed me the remains (below) recovered from amphorae from the Bottega del Garum at Pompeii, which they’d used to recreate Flor de Garum. The signatures they found after a gas chromotography analysis corresponded to the mint, sage, thyme, and oregano listed in a Latin text by Gargilius Martialis, one of the handful of fish-sauce recipes in the classical literature. Funny feeling to stick your nose in a petri dish full of the powdered remains of 2,000-year-old garum!

Sardines were purchased from local fishermen, and fermented in these vessels for 25 days. (Not long enough, and at too high a temperature, in my opinion, but more on that later…)

The result is a very salty, light-hued sauce, with unique herbal notes—Japanese clients in particular appreciate Flor de Garum, which they call the “Umami of the Mediterranean.”

My next move was to meet some of the Gadetano chefs who are using garum in contemporary and traditional dishes. À suivre…