Last week I wrote about the six weeks I spent in the canton of Vaud, in the French-speaking southwest of Switzerland, and some of the amazing foods I encountered: aged gruyère from meadow-fed cows at the Fromagerie Gourmande, Slow Food-approved walnut oil from the Moulin de Sévery, and Servagnin, a rare wine made from a 600-year-old Pinot Noir clone I enjoyed on a century-old train from Morges to Bière.

Those were the highlights, the region’s must-visit culinary pilgrimage sites. But the real revelation for me was the sheer abundance and variety of excellent food I encountered by exploring the region by bicycle. Not surprisingly, there were lots of great bakeries, cheese shops, and restaurants. What I didn’t expect was that, even when I’d missed the retail opening hours, I was still able to fill my backpack with fantastic, high-quality local specialities.

I’d better explain. You’re probably familiar with farmstands—those self-serve sheds or roadside stops where you can pick up a dozen eggs or some firewood, and the farmers trust you to leave a few bucks behind. (I like the ones in Canada’s Prince Edward Island, which offer ten-pound bags of potatoes.) As I began to explore the foothills of the Jura Mountains, though, I realized that Switzerland took the whole concept to a whole different level. And the beauty of it is that, because villages tend to be 3-5 kilometers apart, every time you stop you encounter a new Wunderkammer, a farmstand (often indicated with a “Self-Service” sign) with a different selection of wonderful food.

The first Self-Service I discovered was in the village of Cuarnens. I parked my bike next to a house with a sign advertising “Pomme de Terre.” There was a lot more than potatoes inside, though.

On wooden shelves in the ground-floor room, you could choose from fresh rhubarb, cherries, home-baked bread, fruit syrups, fresh-laid eggs, and yes, potatoes.

You left cash in the green box, and wrote down what you’d purchased on a notepad. (There was also a system for paying with a kind of pre-loaded card, but I never used it myself.) I came home with a pretty nice haul that night—the rhubarb syrup was amazing on the rocks with soda water (and, OK, a shot of vodka), and the rhubarb crumble made for a tart-and-sweet dessert. It all came to 12 Swiss francs, which was about $12.50 US at the time. A lot cheaper than what you’d pay in the supermarkets.

Before I left Cuarnens, I paid a visit to Mozza’Fiato, a cheese shop and factory run by an Italian family that specialized in ricotta, mozzarella and smoked scamorza. (They made a nice change from the hard Swiss cheeses I’d gotten used to eating.)

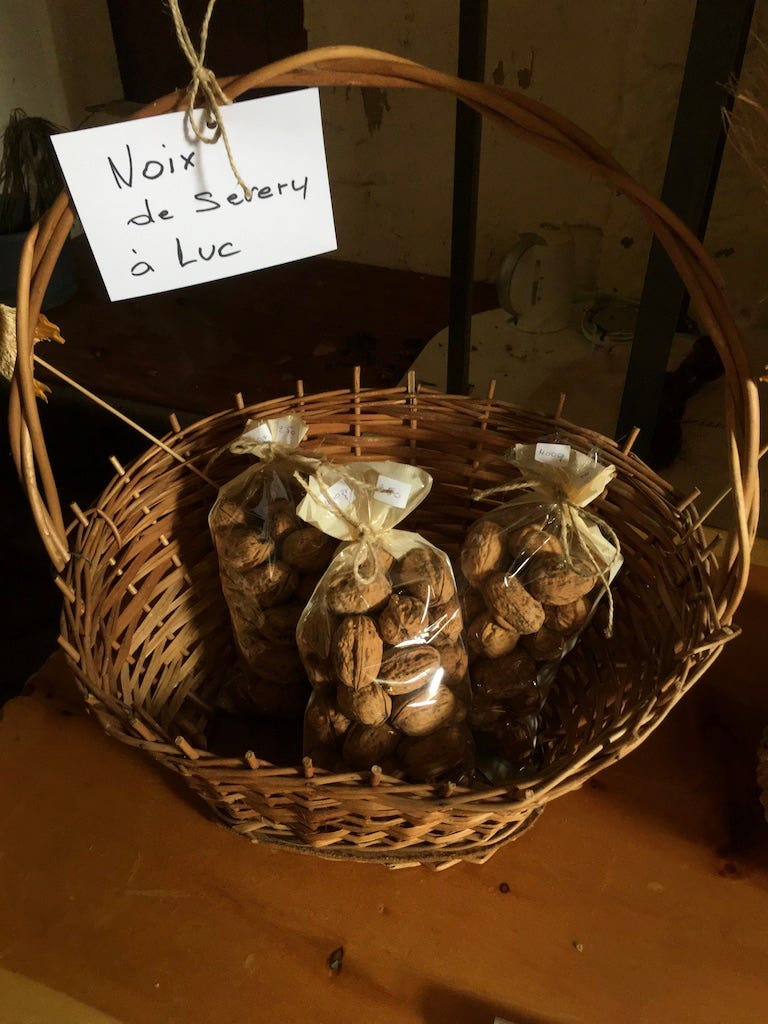

Over the next few weeks, I’d plan out my afternoon bike rides by picking a different village on the map, and seeing whether I could find a farmstand, and what it had to offer. Every one seemed to have a slightly different selection. I spotted this Canadian flag in the village of Sévery, which is known for its walnut-tree orchards, and the mill that presses the walnuts into oil.

Sure enough, one of the things this Self-Service offered was bags of cello-wrapped walnuts. They were the best I’ve ever had, by the way: tender, with just the right amount of tannins.

Part of me wondered if there were many other places in the world where this could happen. The whole set-up worked on the honour system; though the strongboxes for cash were locked and secured, in theory it would be possible to grab what you wanted and leave. I even found a farmstand that offered a crisp artisanal apple cider. In much of North America—hell, much of the world—putting out bottles of self-service alcohol, and trusting people would exercise the appropriate restraint, might end in an epidemic of adolescent debauchery.

Farmstands were just the start, though. I often missed the opening hours of fromageries, but never fear: several cheese shops had vending machines, which allowed you to buy raw-milk, 18-month-old AOC gruyère, all the fixings for fondue, including vacuum-packed new potatoes, and liters of fresh milk at all hours of the night.

There was even, get this, a vending machine for steak tartare. In the parking lot of a gas station, no less. Not the first place I’d choose to buy raw meat, but hell, I guess it works for the Swiss.

There were lots of great little village grocery stores, and I enjoyed patronizing them, and chatting with the cashiers. But they had limited opening hours, which could be frustrating. Fortunately, Switzerland has sorted this with a genius idea: the self-service bodega. That’s right: you sign up with an app, scan a QR code at the entrance, go in and pick what you want from the shelves, and then scan them with a barcode reader and pay with a credit card. (The first time I used one, I forgot my cellphone next to the checkout, and I had to wait until somebody else went in to retrieve it.)

Why do they order matters this way in Switzerland? (To paraphrase Laurence Sterne) It turns out that the cost of labour is very high. So the Swiss have opted for automation. That includes the cheese-turning robot I wrote about last week, but also robo-lawnmowers, which diligently cover every square centimeter of lawns. I found these hardworking Wall-E Horticulturalists rather endearing.

It turns out there’s a handy-dandy guidebook to the Self-Service stands (and farmstands, and self-pick orchards) of Romandy, which you can find in local stores. I definitely got to only a small fraction of them. That’s OK, because I’m already planning my next bicycle trip through the rolling hills of the Jura, and dreaming about all the food I’m going to be stuffing into my backpack.

That will surely include some bottles of clandestine, high-wormwood absinthe. But you’ll read about that next week.

If you’re enjoying these dispatches, I’ll hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription. This Substack writing is an experiment—so far, I’m enjoying it, but I’m going to need some encouragement from readers to keep it going, and to keep the family in milk money.