In the last instalment, I explained how I’d salted sardines, put them in a Mason (Kilner) jar, and found a way to keep them at a constant temperature of about 30 Celsius with a seedling mat, which was placed in a Colman camping cooler.

Before I go on, some people may be asking: what is garum, anyway?

The sauce was beloved by the ancient Greeks and Romans, and ubiquitous in the cookbooks of Imperial Rome. In Petronius’s Satyricon, nouveau riche Trimalchio awes his guests by setting his table with statues from which streams of peppered garum pour over living fish. For the Stoic philosopher Seneca, garum was an “expensive bloody mass of decayed fish [that] consumes the stomach with its salty rottenness.” The few recipes that survive from antiquity describe salted anchovies, mackerel or tuna being left to putrefy in the Mediterranean sun for three or more months.

For many scholars, the takeaway was that the past inhabited by Roman gourmands—notorious for feasting on sow’s udders, ostrich brains and roasted dormice rolled in honey—was indeed an unimaginably foreign country.

Until recently, classicists considered garum to be as extinct as the Dodo. (I’ve heard rumors that scientists are now trying to revive the ancient birds of Mauritius, but that’s another story.)

The Phoenicians, those seafaring masters of the ancient luxury goods market, may be the actual inventors of garum—I go into more detail on its origins in The Lost Supper. You’ll also read about my trip to Cádiz, the oldest city in western Europe, where archaeologists are trying to recreate garum from organic remains found in Pompeii.

I had a few false starts in my attempts to recreate garum—using a yogurt maker didn’t work, because the temperature was too high. Thirty degrees C was the sweet spot. After a few days, the enzymes in the sardines' viscera liquefied the flesh. No water or brine was added—the fish just digested themselves. Autolysis at work!

So this is what the sardines were reduced to after 3.5 months of fermentation: a creamy slurry with bones and scales visible. Question is whether the salt has prevented any toxins (botulism, anyone?) from developing.

I invested in a jelly strainer ($15 at the local kitchen store). And poured the mess into the fine mesh. Best done on the front porch—when the kids were at school! There's already been a lot of "Ewww! Gross!" over this experiment.

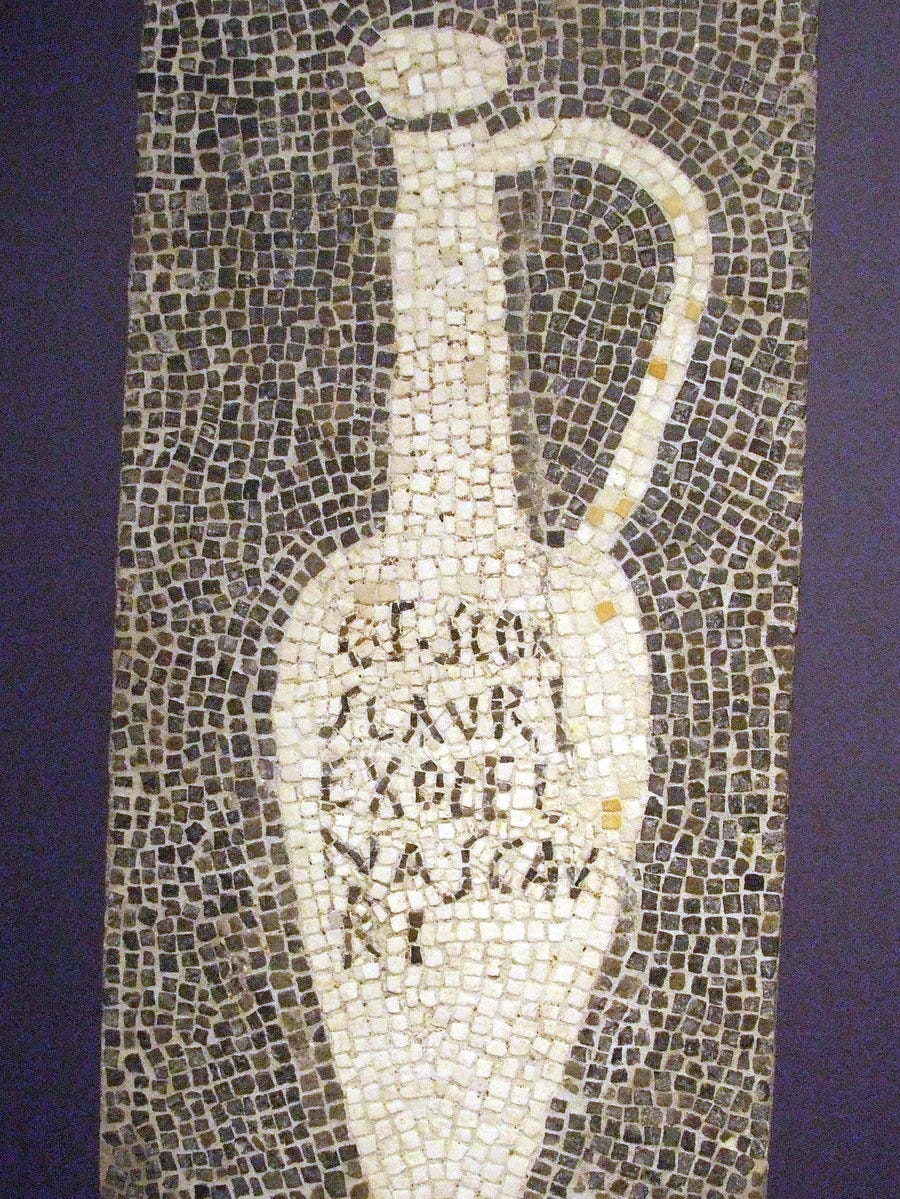

Sally Grainger, the author of The Story of Garum (Routledge, 2020) suggested I rebrine the solids for a week to squeeze a "second extraction." Which is what I did, and got an equal volume of liquid out of it for my troubles. Common practice among value-conscious garum merchants in 1st cent CE, apparently. (Below, mural from house of Scaurus, a wealthy garum merchant in Pompeii.)

The resulting liquid—which the Romans more often called "liquamen" than "garum"—is very similar in colour to this colatura, an Italian sauce made from the drippings of salted anchovies. Colatura, though, isn't fermented (the fish are gutted before salting).

Grainger told me the colour—a coruscating gold—was perfect. The smell is somewhere between colatura and Vietnamese nuoc mam. Intensely fishy, but not off-putting.

And I tasted it—and it was great! Salty up front, but with deep-down umami. As good as the reconstructed version I had in Cádiz, better than most Asian fish sauces. I've been using it in French onion soup, puttanesca sauce, Roman patina of peas (below)—and my kids seem to love it! It also works well with spicy, fermented Korean cabbage—an amalgam I call Silk Road Kimchi.

The secret, in my house, is not mentioning I’m adding it, but that’s another story.

“Ils sont fous, ces Romans!” Pace Asterix and the scholarly consensus—they weren’t that crazy at all, those Romans. Garum and liquamen are secret flavor enhancers, which may explain why there were garum factories from Brittany to Turkey.

Watch this space to learn about how garum blends with the long-lost Silphion of Cyrenaica…