This is about to get nerdy. (But in the best way: food-history nerdy.)

Last winter, I decided to try my hand at replicating recipes from ancient Rome. I’d read that it was nothing like contemporary Italian cooking. Spices were brought in from the farthest reaches of the Empire, and there was a mix of sweet and sour that was more akin to Cantonese cooking than anything found in cucina povera or the other traditions of contemporary Italy.

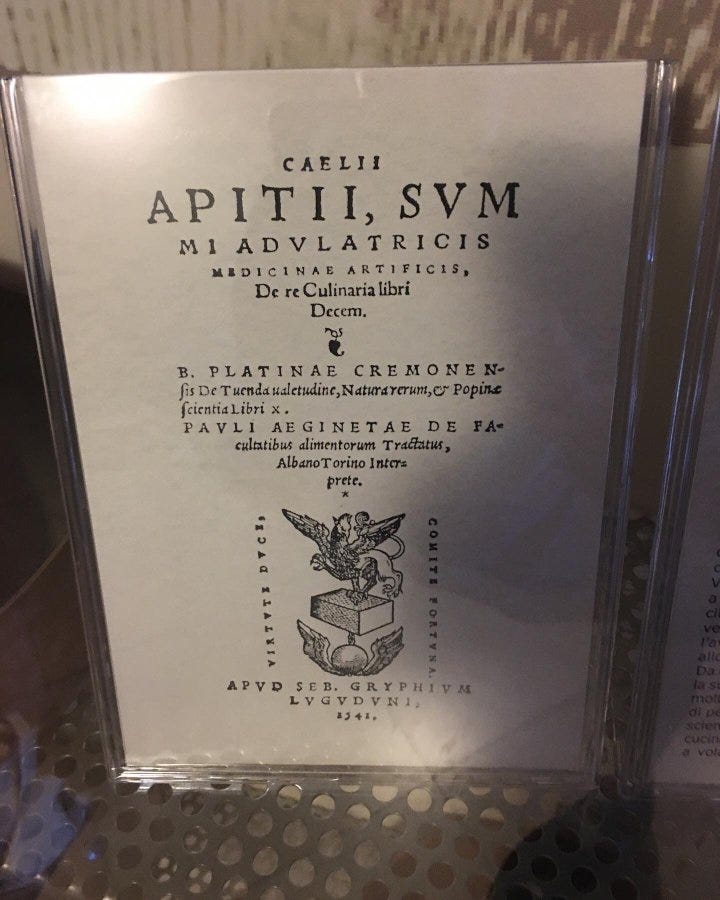

Most of what we know about ancient Roman gastronomy comes from De re coquinara, a compendium of recipes better known as Apicius, after a 1st century epicurean who loved food so much that he was said to have hired a boat to sail to North Africa for the sole purpose of confirming whether the prawns there were better than those in his native Campania.

Consulting an online version of Apicius, I saw that it was more like a handbook, a kind of aide-memoire for expert chefs (most of them Greeks, and probably enslaved), a bit like Louis Saulnier’s Répertoire de la cuisine (which packs 6,000 recipes into 200 pages). Most of the recipes lack measurements or cooking times. Here’s a typical one, for stuffed sardine:

Sarda exossatur, et teritur puleium, cuminum, piperis grana, menta, nuces, mel. Impletur et consuitur. Involvitur in charta et sic supra vaporem ignis in operculo componitur. Conditur ex oleo, caroeno, allece.

Which is translated here:

“The sardine is boned and filled with crushed flea-bane, several grains of pepper, mint, nuts, diluted with honey, tied or sewed, wrapped in parchment and placed in a flat dish above the steam rising from the stove; season with oil, reduced must and [Middle Eastern oregano].”

That sounded pretty good to me—an intriguing mix of sweet, nutty, and umami. But almost every recipe I looked at called for recondite ingredients. I realized that before I cooked anything, I’d have to spend some time stocking my pantry with ancient Roman ingredients—or the closest I could get to them in modern-day Montreal.

Fortunately, I’d already obtained the sine qua non of Roman cookery, garum, or rather, its workaday equivalent, liquamen, which is listed as an ingredient in two-thirds of the 465 recipes in Apicius. (Here’s how I made it myself, by fermenting Portuguese sardines.) I hadn’t yet got my hands on the ultimate secret ingredient of Roman cuisine, a herb thought to have gone extinct under Nero, but I did have the next best thing: asafoetida, also known as hing, a pungent resin from a Ferula plant that grows in Afghanistan. In German, it’s known as Teufelsdreck, or Devil’s Dung. My eldest son Desmond took one whiff and said: “That smells exactly like farts,” and left the kitchen.

Then I began the book research. Patrick Faas’s Around the Roman Table was good as an overview, but not much practical help in assembling ingredients. A Taste of Ancient Rome, by Ilaria Giacosa, was closer to the mark. The best for my purposes was by the English chef and archaeological researcher Sally Grainger, who’d helped me with my garum (and who I’d later meet in Istanbul, a story I’ll tell in another dispatch). Her cookbook Cooking Apicius suggests substitutes for some of the more obscure ingredients in the compendium.

For passum, aged raisin wine, she suggested Muscat de Samos from Greece; fortunately, my Montreal neighborhood has a large Greek population, and I was able to find a bottle at a local liquor store.

I improvised the syrup known as defrutum by slowly simmering 2 litres of red grape juice—an unsweetened Brazilian brand—with 5 dried figs for two hours, until the volume was reduced to a third. Good white grape juice, essential for making caroenum, was harder to find; I eventually settled for Welch’s, and simmered it until it was a third of its original volume, and a nut-brown color. (An acceptable substitute for defrutum, by the way, is Saba de Mosto Cotto, cooked grape must, which I’d picked up in an Eataly in Rome; as dark as balsamic vinegar, and fantastic mixed with soda water as a basis for cocktails.)

Mediterranean herbs were harder to come by; Scots lovage (Ligusticum scoticum) grown on the shores of the St. Lawrence River would have to stand in for regular lovage (Levisticum officinale). Rue, a bitter and mildly toxic herb with a pleasingly funky aroma, came from the garden of a woman in our neighborhood who grows it to keep the squirrels away from her tomatoes.

Other spices that appear in Apicius were already on my shelves, or obtained by a bike ride up to the Épices de cru store in Jean-Talon Market: savory, bay berries, myrtle berries, green coriander, and top-quality pepper (the Romans were pepper fiends). Ethné and Philippe de Vienne, the “spice hunters” behind the shop, had even concocted an Apicius Blend (see above), which I could see myself using in a pinch, as you would a Garum Masala when you were feeling too lazy to roast and grind your own Indian spices.

By then, I felt like I could cobble together a mise-en-place for many of the recipes in Apicius. What to choose, though? Like the Cantonese, the Romans seemed to enjoy eating anything with four legs that wasn’t a table, and anything that flew and wasn’t a kite. We live in a more populated world than they did, and feasting on wildlife is frowned upon: besides, the thought of eating scalded flamingo, dormice rolled in honey, and sow’s udders left me cold. But I still wanted to experience the flavors and aromas of ancient Roman gastronomy. I’ll tell you about some of my experiments in the next dispatch…

_______

I’ve been writing these dispatches for a few months now, and I really appreciate everyone’s interest! As of next week, I’m going to start writing posts intended for paid subscribers. (Free subscribers will still receive occasional dispatches by email.) If you want to continue receiving all the dispatches, please consider a paid subscription; this will also give you access to the archives, and also help me continue my culinary experiments.