Ever heard of pulque? I was familiar with the name. Maybe I’d read about the drink in Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, a reference to a limbo-like, sawdust-floored pulqueria, where banditos and ladrones cursed, spat, sharpened machetes and sipped a loco-making brew. But before going down to CDMX (Mexico City), I’d never tasted the stuff. The closest I’d got was mezcal—first consumed, with disastrous results, on a teenage trip to Tijuana—a smoky, mind-altering liquor which comes from the same plant.

There’s an excellent reason not many people have heard of pulque. It doesn’t travel, and it can’t really be bottled. Pulque is made from the aguamiel, or sap, of the maguey plant, also known as the agave. Those are the bristly, Jurassic-looking cacti you seee in the badlands, which can grow to huge sizes. Unlike mezcal, pulque is fermented, not distilled. Pulque-makers hack into the core of the cactus, and scoop out the aguamiel, which is allowed to ferment for a couple of days.

It’s a living, volatile liquid, which goes off quickly after it’s reached its peak. Which makes it a very Mexican, and very anti-capitalist beverage: you have to drink it fresh, which means you have to be within a day’s shipping distance, preferably less, of where the maguey grows. No way Coca-Cola is going to commodify pulque.

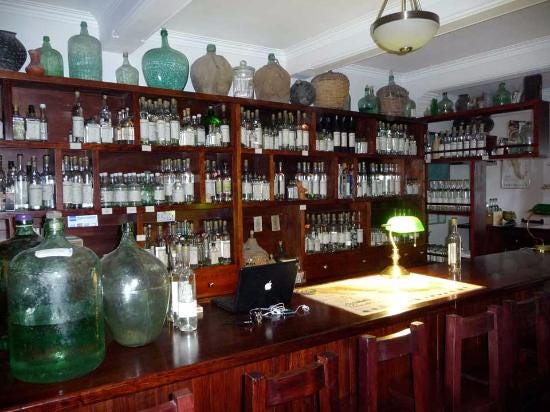

I’d got the whole mezcal experience in Oaxaca, including a barely-remembered trip to the Mezcaloteca, a “library” of mezcals, with hundreds of different bottles on the shelves, and sarcastic hipsters behind the bar to guide you through a tasting. One thing I retained was the sheer number of distinct varieties of agave, all of which are purported to produce a slightly different tasting mezcal. I came home from that trip with a couple of bottles of “single-village” mezcal,. One of them remains half-empty (definitely not half-full), a feared and adored relic, in a Tantalus in our dining room.

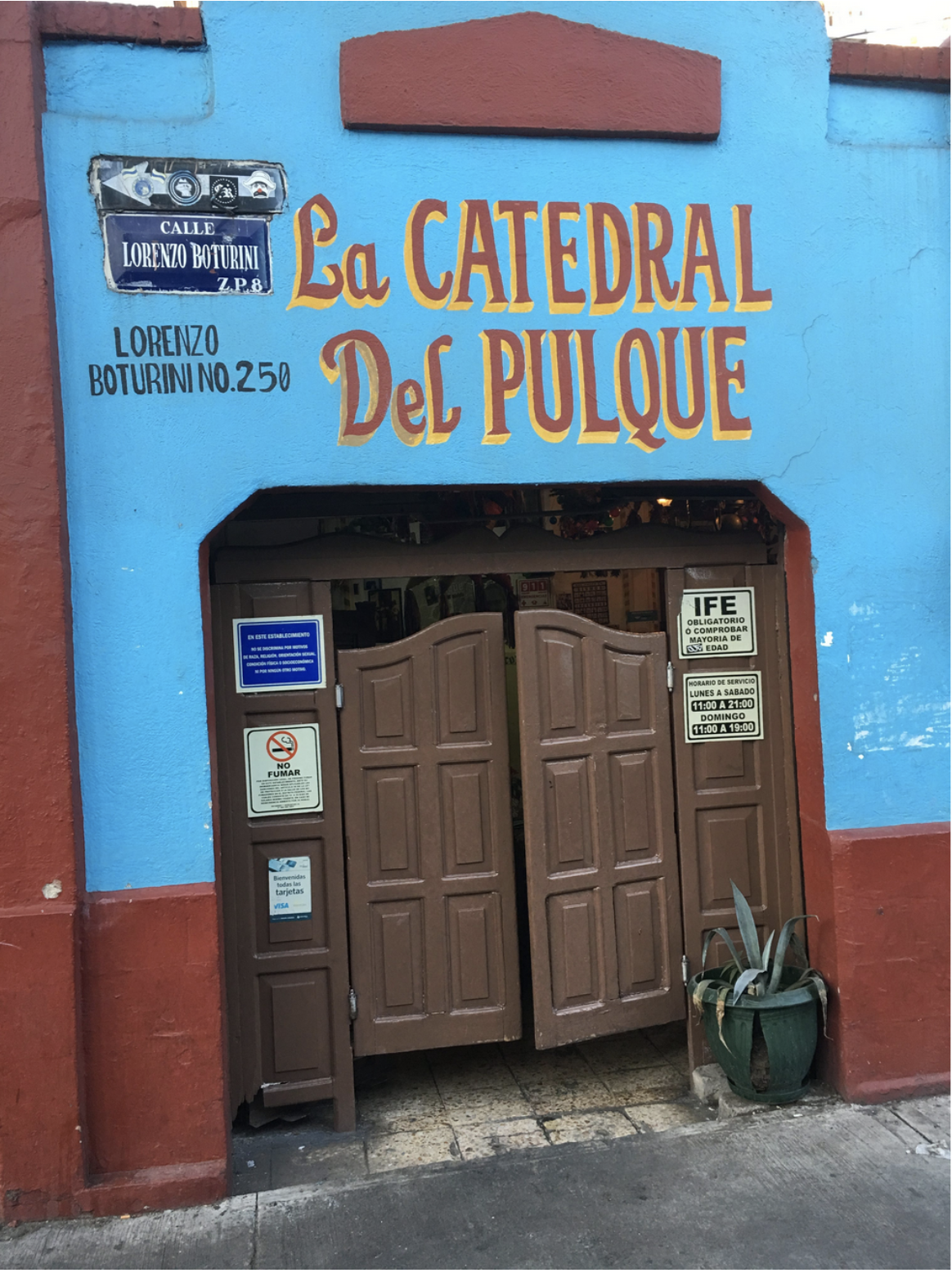

The first pulqueria I went to, in the company of my interpreter Alfredo Francis, was La Catedral del Pulque in the Obrero neighborhood of CDMX (see photo above). It had everything I was hoping for: swinging wooden doors, a crepuscular interior, and crazy murals on the interior walls—including a huge Michelangelo tribute featuring a googly-eyed God handing an equally loopy Adam a bowl of white liquid. After ordering two mugs at the bar, we sat down at a table with two young women working on their own glasses—the whole vibe of pulquerias, I discovered, was convivial, communal, and non-aggressive (pretty much the opposite of your standard alcohol-themed bar).

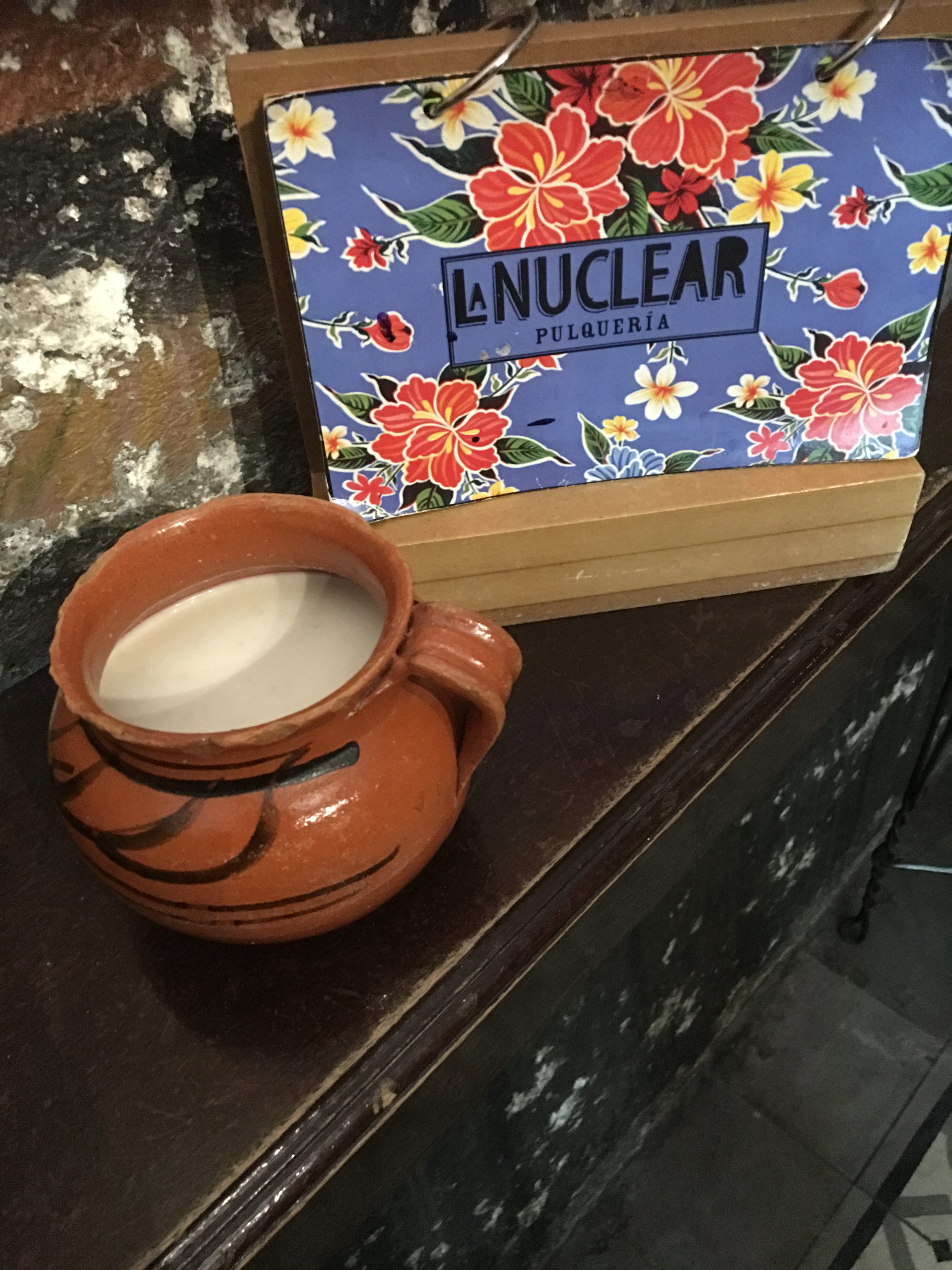

The basic unit, apparently, was the litre. Which is a lot of liquid to swallow. There were several options, including tomato-flavored (with salt on the rim), “nuez” (nut, not sure what kind), a variety of fruit—pineapple, lime, mango—and iguana, which I didn’t dare ask about. I started with half a litre of “natural,” unflavored pulque, for 30 pesos ($1.64 US). It was thick, viscuous, milky-looking—opaque, but with a kind of inner glow. I had a sip, then a gulp. It was creamy, yeasty, a little sweet, and most definitely alive. Its consistency was very unusual: it was gooey, even sticky, so that strands sometimes ran from lips to glass. I thought of natto, the notoriously snot-like and pungent fermented soybeans that are eaten as a breakfast food in Japan, though pulque isn’t quite that thick, and often comes with a nice head of froth.

There was ground cinnamon on the table, to sprinkle a little flavor on top, but also a shaker of bicarbonate of soda. Alfredo explained that this was to combat the burping that came when you drank large amounts of pulque. “It continues to ferment in your stomach after you drink it,” he told me. “That means that you can still be getting drunk hours later.”

Except, after my second half liter, this one made with avena (oats), I wasn’t feeling drunk. There was no sense of being out of control, no mounting anxiety and release, no ego-pumped aggression. Just a sensation of edges blurring, and an agreeable sinking into the ground. It reminded me of the one time I’d had real kava kava from the South Pacific (another hard-to-transport intoxicant): a feeling I was becoming one, in a very basic but pleasant way, with my reptilian brain. There were some very well-muscled, gangster-tattoed guys at a corner table; I’d thought they might look askance at a gringo-turista in the bar. Not at all. They had big, sloppy smiles on their faces, and seemed sunk in a blissful torpor which, the more I drank, the more I understood. My ride on the Metro back to my hotel in Condesa that day felt more like a wonder-filled and relaxing snorkel through body-temperature water.

Pulque was reviled for a long time in Mexico, because of its associations with indigenous culture, and the malinchismo of a Eurocentric middle class. Beer, la bebida de moderación, was considered the up-to-date drink. That’s changed lately, and in Roma Norte and Condesa I found pulquerias frequented by foreigners and Mexican hipsters. At La Nuclear, they served pulque in pottery cups, and proudly displayed the 50-litre plastic containers in which the drink is fermented and transported from the states of Jalisco and Hidalgo.

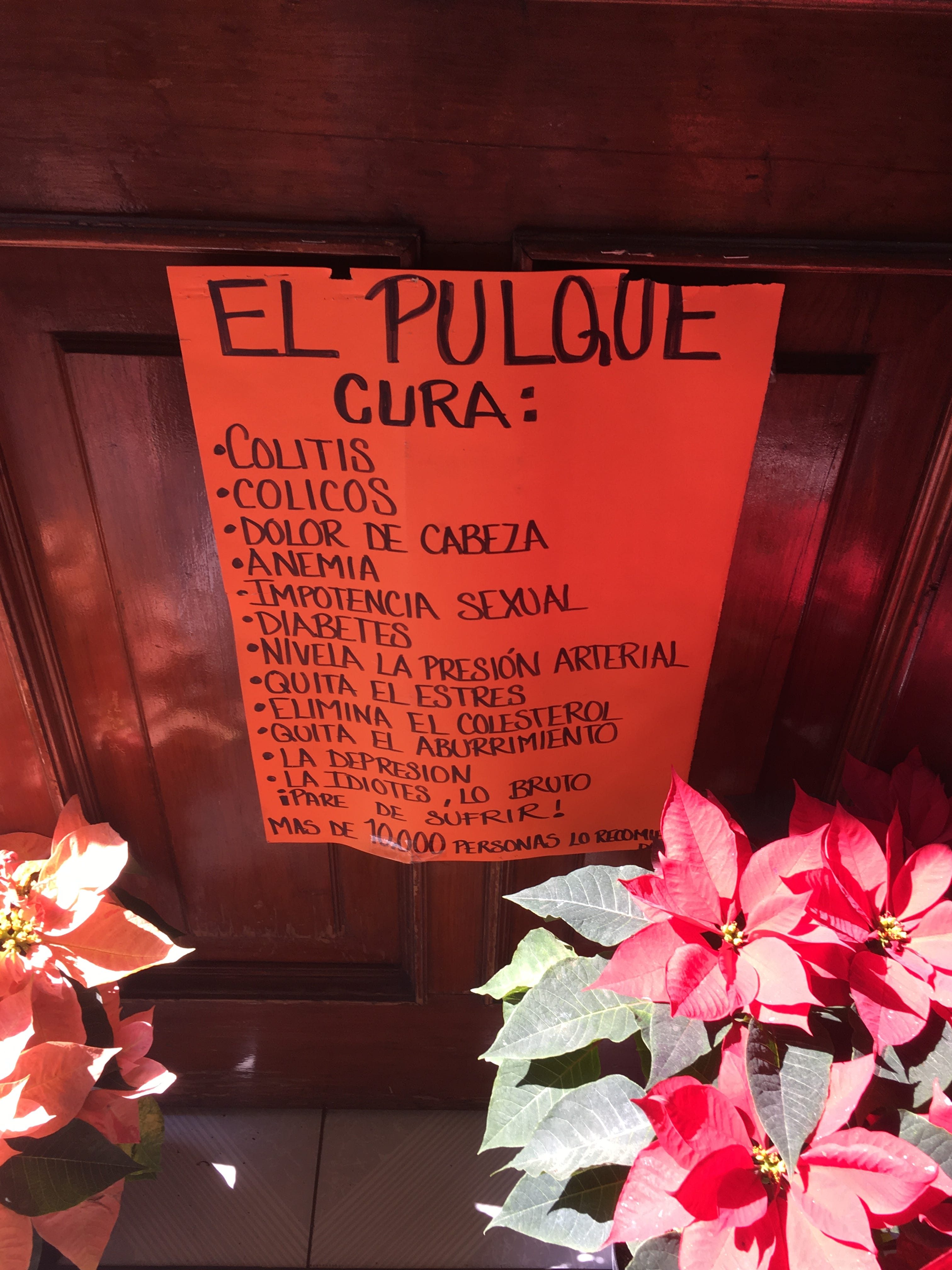

At Don Chon, near La Merced market, a restaurant that specializes in pre-Hispanic cuisine (from armadillos to edible insects), there was a poster touting pulque as a cure-all, of everything from colitis to depression. For what it’s worth, chemical analyses turn up Vitamins B, C, and D, lots of carbs and amino acids, iron, phosphorus, and alcohol (though no more than 3 or 4% by volume). And there is definitely something else in there—whatever it is that imparts that indescribable body buzz. (“For me,” mused Alfredo at one point, “it’s more a sativa feeling than an indica feel.”)

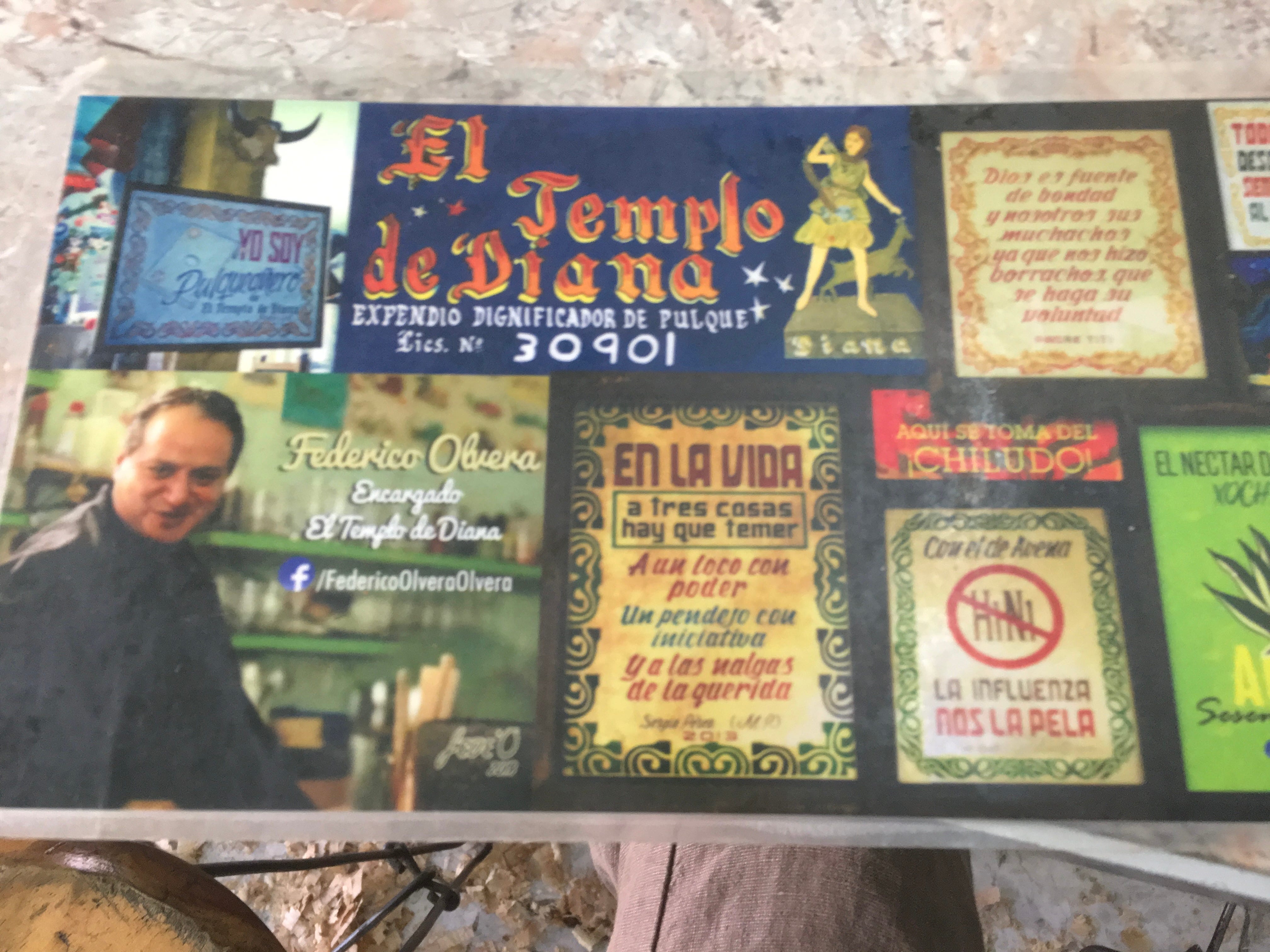

My favorite pulque experience was my last one. I’d spent a sunny Sunday morning on a trajinera, a canal boat, in Xochimilco, and asked my ramero, or oarsman, Dylan, where I could find a pulqueria nearby. He walked me over to El Templo de Diana (I invited him in, but he explained that at 18, he was too young to drink pulque). I ordered a natural grande, for 39 pesos, the cheapest price I’d found yet. There was sawdust on the floor, a borracho slumped in the corner, soccer on the TV, and a trio of nurses, in their blue scrubs, enjoying a lunch-hour litre of fermented cactus juice. And then, that gradual feeling of complete relaxation, of not really wanting to be anymore else.

Here’s the photo I took of my last glass of pulque in CDMX. I want more. But I can’t get it here. I’ll have to go back to Mexico. Which is as it should be.

If you’re enjoying these dispatches, I’ll hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription. This Substack writing is an experiment—so far, I’m enjoying it, but I’m going to need some encouragement from readers to keep it going.