This week I’m going to take you to a very special place, located on a magical archipelago known as the Magdalen Islands—or, as they’re known in Quebec, les Îles-de-la-Madeleine. The first time I went there I thought I’d stumbled on a Canadian version of Brigadoon, the Scottish village in the Technicolor musical of the same name, a place said to appear for a single day once every century.

What brought me there on my first visit was a fish—a smoked herring, marinated in oil and vinegar, which sent my tastebuds into the culinary equivalent of a swoon. When I asked my fishmonger where he’d found this miracle fish, he said they’d come from the Magdalens, eight islands in the gulf of Canada’s St. Lawrence River, closer to the coast of Newfoundland than to Quebec’s Gaspé peninsula. The archipelago has only 13,000 year-round residents, most of them francophones of Acadian origin. In spite of the small population, the Mags, as they’re often called, have a reputation for having some of the best food—especially seafood—on the east coast.

My flight from Quebec City, with a stop at the little airport in Gaspé, offered a stunning overview: as we banked towards the landmass of the islands, red cliffs and green meadows outlined by white sand and turquoise sea conjured up an Ireland unmoored, as if the emerald isle had drifted down to tropical waters.

I knew exactly what my first stop was going to be: the Fumoir d’antan, the source of the fish that had hooked me, like a halibut on a longline, and pulled me to the islands from Montreal. The fumoir is a smokehouse, where fish caught in local waters—there are still over 300 working fishboats on the Mags—are processed and smoked for export. There used to be many of them. The Fumoir d’antan, located next to a small harbor and the facilities of Trésor du large, which raises intensely flavorful deep-water oysters, is the last smokehouse standing.

I was greeted by Benoît Arseneau, a barrel-chested man-mountain who invited me to take a seat at a picnic table. “The Arseneau family arrived on the islands in 1755,” he told me, “after the grand dérangement. We’re Acadians, originally from Poitou, in France.” The expulsion by the British of more than ten thousand French settlers from their farms in Maine and the Canadian Maritimes, led to a diaspora that would eventually people the bayous of Louisiana with Cajuns. Some Acadians found a home on the Magdalens, one of the few places they could maintain their Catholicism and continue to speak French. Arseneau’s grandfather built the fumoir in 1940, which, together with 40 other smokehouses on the islands, would cure ten thousand pounds of herring each spring. When he was a child, he saw beaches white with herring spawn, and seas darkened by the deep-blue backs of the fish as they swam towards thousand-foot-long shorefront nets. The smoked, salted fish were exported to the Caribbean to provide cheap nourishment for the cutters of sugar-cane.

“American and European fishermen destroyed the stock,” he tells me. “The first and only time I saw my father cry was in ’seventy-six, when he decided to close the smokehouse.”

For Arseneau, demolishing the family business would have meant erasing part of his heritage. He and his brothers banded together keep to keep the smokehouse going, and now it processes the catch from the waters off Newfoundland and New Brunswick. Leading me through swinging wooden doors into the hangar-like building, he reached to the rafters, where whole fish, iridescent scales varnished with smoke, dangled by the gills from metal rods. The smoking process, done with maple wood, begins on June 24—the fête nationale of Quebec—and takes six and a half weeks. Arseneau handed me a filet—it was additive-free herring jerky, shot through with the irresistible smokiness I’d first tasted in Montreal.

At the counter of the Fumoir’s shop, he offered me skewers of mackerel, scallops, cod, and salmon cured in a mechanical smoker. As I savored the intoxicating mix of smoke and umami, I wondered aloud why the Mags punched so far above their weight when it came to food.

“Madelinots have always taken pride in doing things well,” he told me. “We get eighty thousand visitors a year, and we like to share the best of our knowledge with them.”

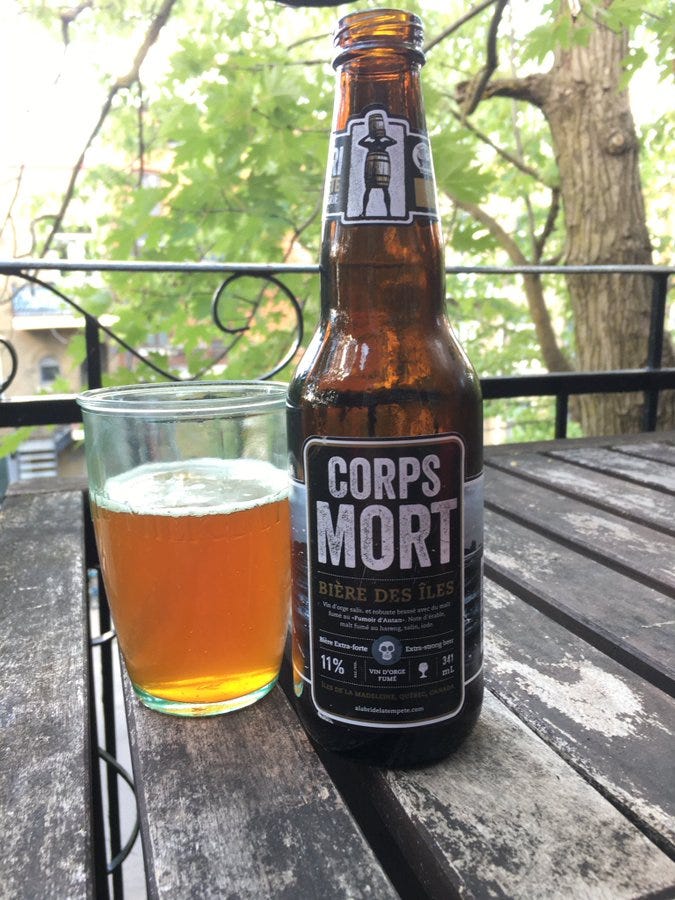

Local producers, he points out, also take pride in sharing their know-how and resources. He asked me if I’d like to have a drink to accompany my seafood—and didn’t have to ask twice. He uncapped a bottle of Corps Mort—a barley wine, which packs twice the alcoholic punch of a lager—made by local microbrewery À l’abri de la tempête.

“Can you taste the smokehouse?” Arseneau asked. I could: it was as if the essences of maplewood and fatty fish, the latter purged of any cod-liver-oil unpleasantness, had been alchemically distilled into a drinkable elixir. During the lengthy smoking process, he told me, fat from the suspended herring dripped into piles of malted barley, which the island’s only brewery then turned into what the French call a vin d’orge.

“It’s almost animal, this drink,” Arseneau chuckled. “With smoked fish, it’s the perfect marriage.”

Indeed. Corps Mort is the bottle I seek out at home in Montreal when I want to be reminded of the taste of the Mags—that, and a half dozen herring from the Fumoir d’antan. At a deep level, the people of les Îles-de-la-Madeleine understand intensity of flavor, which is the quality that gets me out the door and adventuring into the world. I’ll share some more of the fantastically tasty food of the Mags in future Lost Supper dispatches.

_____

…I hope you’re enjoying these dispatches! This one is free, but not all of them will be. Consider becoming a founding member or upgrading to a paid subscription to continue following all my culinary adventures.